BRMs, When It Comes to Value Optimization, Think Snakes and Ladders

As a BRM, you are the primary actor in progressing initiatives from ideation through to operation, ultimately landing at value optimization. The underlying objective throughout is to ensure that the intended business value has been realized.

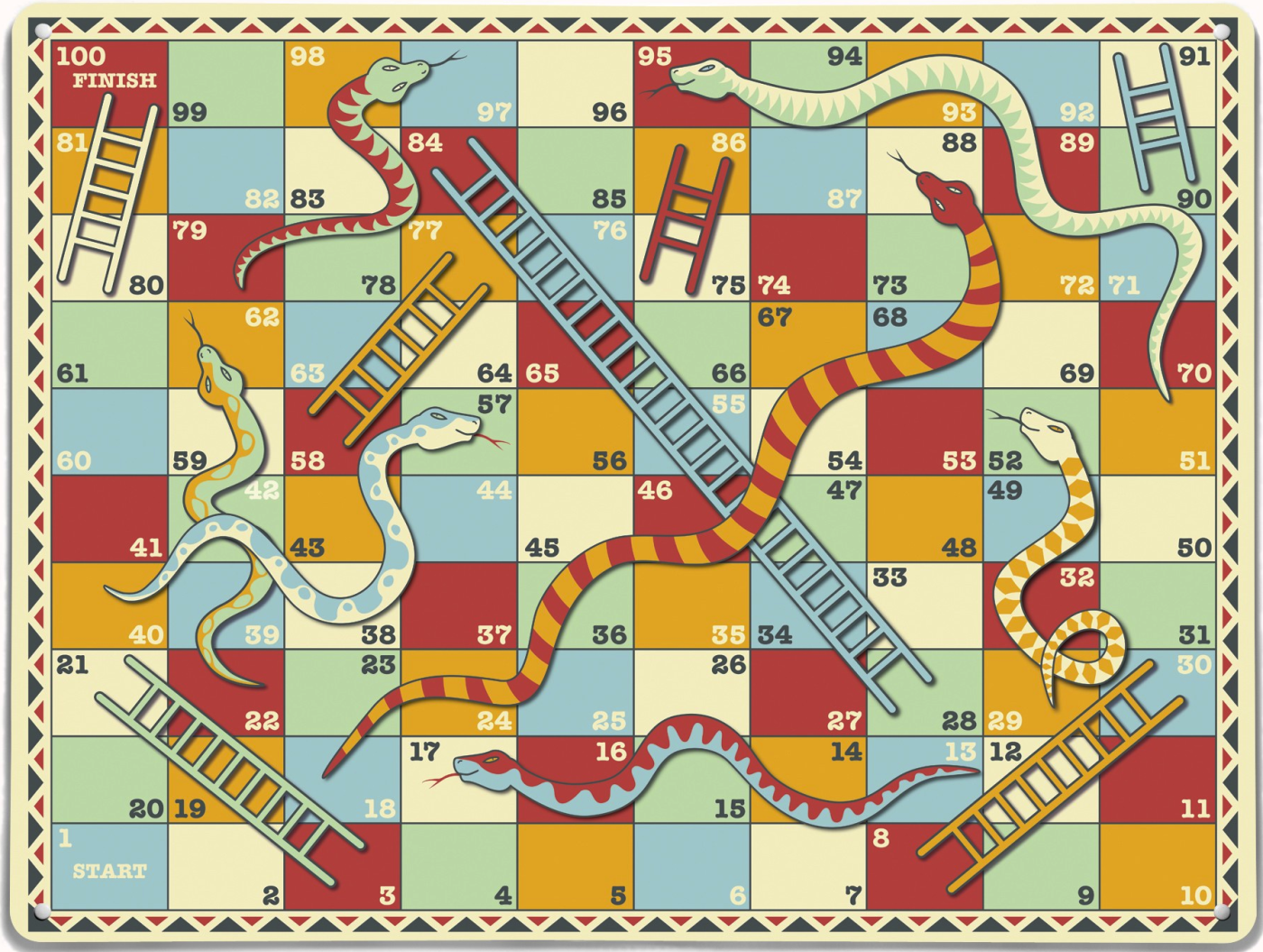

Without proper attention, there are many pitfalls that may delay, reduce, or jeopardize the successful realization of value. Since you as the BRM play a significant role in driving things forward, it is worthwhile to think of the child’s game snakes and ladders to help you better understand the process.

The game actually originated in India, where it had its roots in morality lessons. A player’s progression up the board represented a life journey complicated by virtues (ladders) and vices (snakes); the ladders represented virtues such as generosity, faith, and humility, while the snakes represented vices such as lust, anger, murder, and theft. The moral lesson of the game was that a person can attain salvation (Moksha) through doing good, whereas doing evil will ultimately lead to rebirth to lower forms of life.

Image source: Vikas Acharya

Just as the English eventually came across the game and adapted it for entertainment purposes, the game’s basic concept can also be applied to progressing initiatives.

Most organizations have a gating methodology to govern project initiatives, in which the gates are wherever stakeholders engage to assess and provide input on the initiative from their perspective or stake. Properly engaging stakeholders at the right time helps us progress from the beginning to the end, and if our initiative does not raise any flags or require oversight from a particular stakeholder interest (such as security or architecture), then we gain that ladder and progress more quickly.

On the other hand, if we fail to engage a stakeholder appropriately—or too late in the game—we catch a snake that takes us back a number of squares. In fact, the phrase “back to square one” is thought to have originated in the game of snakes and ladders.

Some examples from earlier in my career:

I was the business analyst/program manager charged with ushering an initiative through the Value Management process for approval, project structuring, and initiation. As we were about to take the initiative to the Value Management Board for their approval, one of members of the Board asked us to come and review the solution concept and business case with some of his key influencers. When we came into the room to present across the table, there was a board member and four of his “henchmen”—or at least that’s exactly how it seemed.

One of them had filled our document with yellow sticky notes, and after a quick introduction by the board member, he dove into us with questions like we were a hunk of meat. Needless to say, the outcome was that we were knocked back a few squares to address their concerns, which delayed our approval.

I was working in the Office of Architecture in a client organization. I was asked by the manager of the office to review a document that one of his architects had created regarding a desktop upgrade and renewal strategy. Thump was the sound of the thick document hitting my desk.

I opened to the first page to see the author’s name, but no other reviewers of version 1.0. (My first warning sign.) After spending some time going through the table of contents and the first part of the document—with lots of red ink—I returned to the manager’s office and asked if he wanted an editorial review or a critical review.

If the answer was “a critical review,” it was much too late for that. This person had put their heart, soul, and sweat into this, and to get severe critical feedback at this point would be a huge blow.

In our gating methodology, we can define the key stakeholder groups (such as business management, business users, security, compliance, architecture, and operations) and their interests. Each group’s interests would be defined as a set of criteria and questions. The business’ interests would likely be criteria around strategic alignment, funding requirements, approval chain for various domains, etc. These criteria could be captured as a set of questions to be asked of all initiatives.

For example, from a security stakeholder perspective, some questions would likely be:

- Does the solution involve online transactions?

- Does it involve sensitive information?

- Does it require integration of multiple systems?

If the answer to all of the questions is negative, then the initiative catches the security “ladder.” These questions would then be revisited at subsequent gates to ensure the answers were the same, and if so, there would likely be minimal security oversight required. For each positive answer, there would likely be a further set of stakeholder questions asked that would require that the detailed security steps be followed (no ladder).

Navigating individual steps may seem tedious, but if the stakeholder interest requires it, then the steps must be followed.

Navigating individual steps may seem tedious, but this solution is far better than the alternative——the initiative progressing along without engaging the required stakeholders at the right time, and later catching a “snake” to revisit and address that interest.

After all, this solution is far better than the alternative—the initiative progressing along without engaging the required stakeholders at the right time, and later catching a “snake” to revisit and address that interest. This would add unnecessary costs, delays, bad visibility, and further repercussions that tend not to sit well with business partners.

Ultimately, and at the extreme, the best answer for some initiatives is that they should be stopped or significantly revised according to the interests of one or more stakeholder groups.

Engaging those stakeholder groups effectively is an important key to success. There are various specific techniques defined in the BRMiBOK that can help you with this, such as the Portfolio Management Process, the Value Plan, and Stakeholder Mapping.

As a BRM, you should understand the rules and stakeholders of snakes and ladders in your organization—after all, you will be the primary one holding the dice.

Bob Swan has over 30 years of business and IT experience across a broad spectrum of organizations and industries. Residing in Calgary, Alberta, his career spans from the introduction of personal computers into the business environment in the mid 1980s to the complexity that is the IT environment today. He holds CGEIT certification in Governance through ISACA, ITIL Expert and BRMP, as well as degrees in Business and Economics. You can contact him at [email protected].

Good article, I like this as a metaphor for the value management process.